Long Term Agenda Backgrounder

Introduction. As organizers, we engage in the day to day struggles that can make a difference in people’s lives. And yet, these struggles can put us in tension with our longer-term goals, especially our transformational goals and vision. At GPP, we have been grappling with a question that political thinkers and activists have tried to address since the late 19th century: how can reforms add up to more fundamental changes? As the groups we work with identified bigger, long-term goals, we needed a set of tools that would help them navigate this tension toward getting their campaigns to add up to something greater than the sum of their parts.

Our movements needed an overall picture, or map, that helps us get there from here. That’s what a “Long Term Agenda” (LTA) is meant to be –– the overall picture that helps groups in an alliance or network orient their work together toward achieving transformational goals. It identifies the larger, shared, aspirational goals and then provides a framework for working backwards, then forward along pathways. The larger goals are bold enough and far-reaching enough to be transformative, and at the same time, within a time horizon and scope that is recognizably actionable. It is not a linear process, or even a finished product. It is a way of putting a theory of change into practice, and making adjustments to practice, as we go along, as conditions change, as opportunities expand and contract, and so on. What follows is a description of the core components of this overall picture.

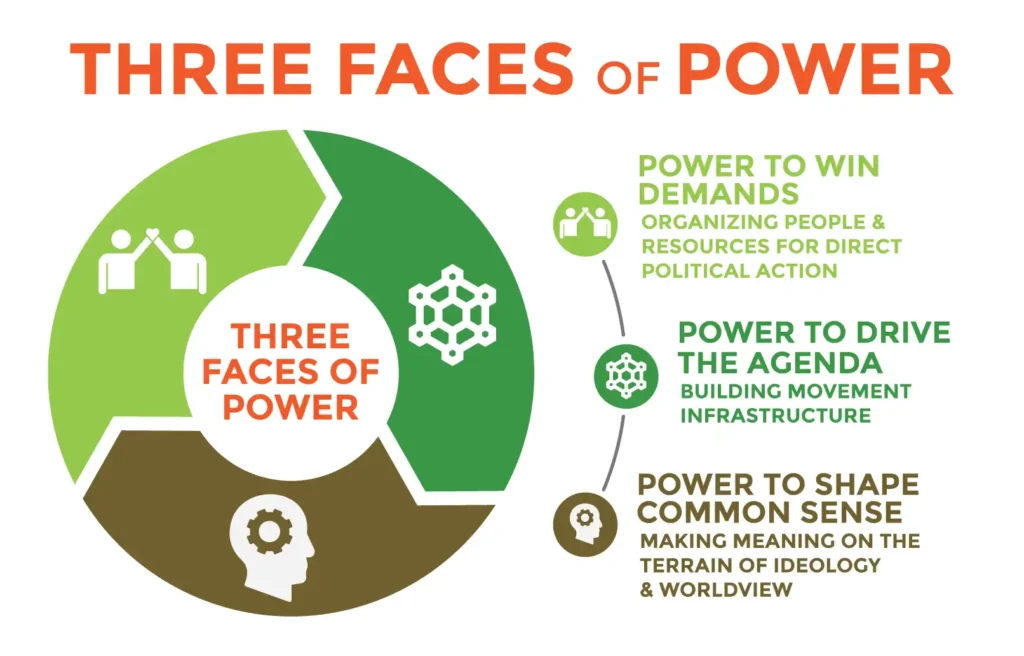

I. Relationship to the Three Faces of Power

The Three Faces framework has served as an introduction to strategies for intervening and shifting these structures of power: class, race and gender, within economic, social and political structures.

The first face refers to the ways in which groups mobilize to target lawmakers, legislatures, corporate boards and CEOs, Wall Street, and sometimes, the courts, mostly through direct action, advocacy and lobbying. The targets for direct action are in the most visible decision-making arenas in society. A lot of what can happen in these visible arenas is shaped and constrained by the 2nd and 3rd faces of power.

The second face encompasses the need to build forces that can make the shifts through what we sometimes have referred to as the movement infrastructure. These include groups with bases, who can engage members deeply around longer-term goals, not just one-off issue campaigns. It also includes the cross-organizational and cross-sector spaces where leaders work together on movement-level goals and strategies. The infrastructure also includes a wide array of organizations that provide resources to base-building groups, alignment tables and networks (resources that include research, communications, policy development, training support, as well as financial support); ideally, and eventually, also progressive segments of political parties. To get a handle on the notion that our organized forces could move an agenda, we need to project a picture of what it looks like if you make major shifts; 5, 10, 50 years from now.

When we started out working with statewide coalitions in the late 1990s, they were struggling with what one person called ‘coalition gumbo:’ a coalition for every issue. There was no real

work on alignment. One way we intervened was with “What’s on the agenda, what’s off the agenda.” As groups started to shift from gumbo to building infrastructure, this created space for talking about shifting the political agenda. Putting something big on the agenda is hard to do through first face of power interventions alone. But you can think about how to fight, over time, to get something on the agenda. The tools change, as movements and conditions change.

The 3rd face brings in the ideological conception, the analysis, and the vision that propels us toward the transformed structures. On this terrain of ideas, narratives compete to give meaning and purpose to political struggles. Part of the analysis involves being clear about what we are up against, and part of the organizing and practice involves shaping our own narratives. The 2nd and 3rd faces are intertwined, but sometimes, the process of separating them out conceptually can reinforce a tendency to treat these as separate spheres. It makes sense that things don’t neatly happen sequentially; a lot of the strategy work includes elements of ideological work, whether or not people name it as such. While GPP’s experience in applying the 3 faces framework to organizing was mostly with groups that had been more 1st-face oriented, now that we also are starting to work with groups that focus more in the 3rd face, and ideological struggle, we are finding that this framework also helps these 3rd face groups see how they can help advance more strategic campaign and electoral work in the first face and help build stronger, more ideologically coherent alliances that move agendas in the second face.

We have found that the LTA really works best with some grounding in the 3 faces of power, understanding the need to shift the agenda, and the ideological work that is involved in making these shifts.

II. Relationship to a Conjunctural Analysis

A conjunctural analysis, sometimes called ‘naming the moment,’ is an analysis of the current period that looks at the social, political, economic and ideological elements that are in play, with special concern for the interactions between them. During a conjunctural crisis, the different social, political, economic and ideological contradictions that are at work in society come together to give it a specific and distinctive shape. A conjunctural analysis can help us get a handle on the range of potential outcomes in a moment of crisis. It forces us to look at many different aspects, in order to see what the balance of social forces is and how we might intervene.

Crises are moments of potential change, but the nature of their resolution is not given. It may be that society moves on to another version of the same thing, or to a somewhat transformed version; or, it may be a moment when relations can be radically transformed.

Consider the conjunctural crisis of the mid-1970s. The crisis – characterized by growing inflation, economic stagnation, unprecedented global competition, energy shortages, declining wages, and rising unemployment – was resolved to the benefit of global corporate and financial interests, with a return to market fundamentalism and a diminution of the informal social contract

among business, labor and government. One could argue we’ve been in a conjunctural crisis since the Financial Meltdown of 2008. But, what kind of crisis is it, exactly?

This kind of interrogation of the moment sets us up well for working together on a longer-term picture for more radical transformation. An LTA is about approaching the work more strategically, with a longer time horizon. Both the process of shaping an LTA and the picture that emerges, are strategy tools, or maps that help us hold the long-term as we address the possibilities of each moment. It is meant to be flexible, so that we can make adjustments that are informed by current conditions.

III. Key elements of the LTA

To motivate a process of crafting an LTA, it is helpful to talk about the Right’s version; something we extrapolated from our analysis of how different parts of the corporate-conservative infrastructure made advances, over several decades, with a shared vision of where they wanted to be and how they wanted to govern. This also included analyzing their ideological discipline in using their core ideological themes, weaving them through all of their narratives, and driving them into popular political consciousness. We started with the Powell memo. We looked at pathways re. privatization, deregulation, etc. And we wove in the ideological elements that held it all together. When we started, people were not talking so much about neoliberalism. But now, it makes sense to look at the start of the neoliberal shifts, in the mid 1970s, as a way to trace their trajectory to governing power.

Here’s one way of picturing the Right’s long-term approach:

A. ComponentsoftheprocessofcraftinganLTA:

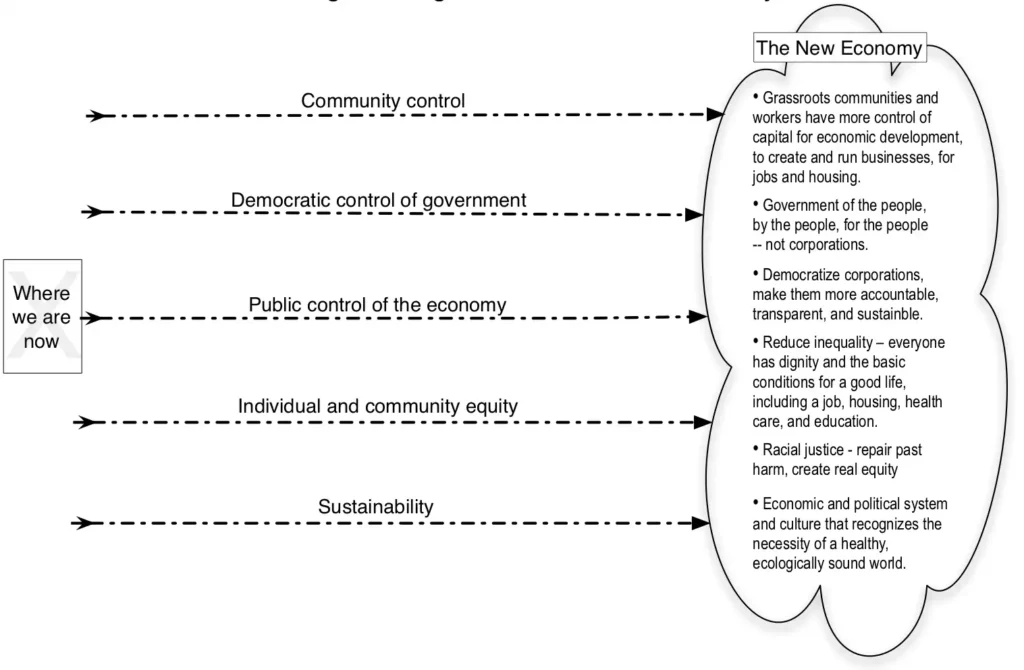

1. Where we want to be. This is our vision of where we want to be, 10 years out (or 40 years,

if that is possible). We will put this into the picture as what will orient our work.

2. Game-changing reforms. We see these as guideposts that move us along the way – things we can accomplish within our timeframe (let’s say 10 years). We have called these ‘structural reforms,’ and we’ve suggested that a reform is ‘structural’ if it has the potential to shift power and resources to communities, workers, and excluded constituencies. Not every reform will be ‘structural;’ but for this step, we like to encourage people to name everything they are thinking about, get them all down, then sort them out. Later in the process, as we sort them, and apply analysis of current conditions, these will get sorted out into ‘stepping-stones,’ or ‘milestone reforms,’ or ‘structural reforms.’

3. Pathways. These are the major fronts on which we are moving toward ever-greater reforms; the paths, or pathways, that help orient our efforts to move reforms that shift power in every social and economic sphere. These pathways overlap, and the best reforms are the ones that can cut across paths. But naming and distinguishing them can help flesh out the overall picture. It also helps groups in an alliance see more clearly how their issue areas fit into the overall picture, as part of moving the agenda as a whole, through their areas.

The pathways may look different, depending on the issue areas that a group or network is focused on. And the pathways also will reflect the current conditions.

Here’s an example of ‘pathways’ related to long-term goals, developed with People’s Action:

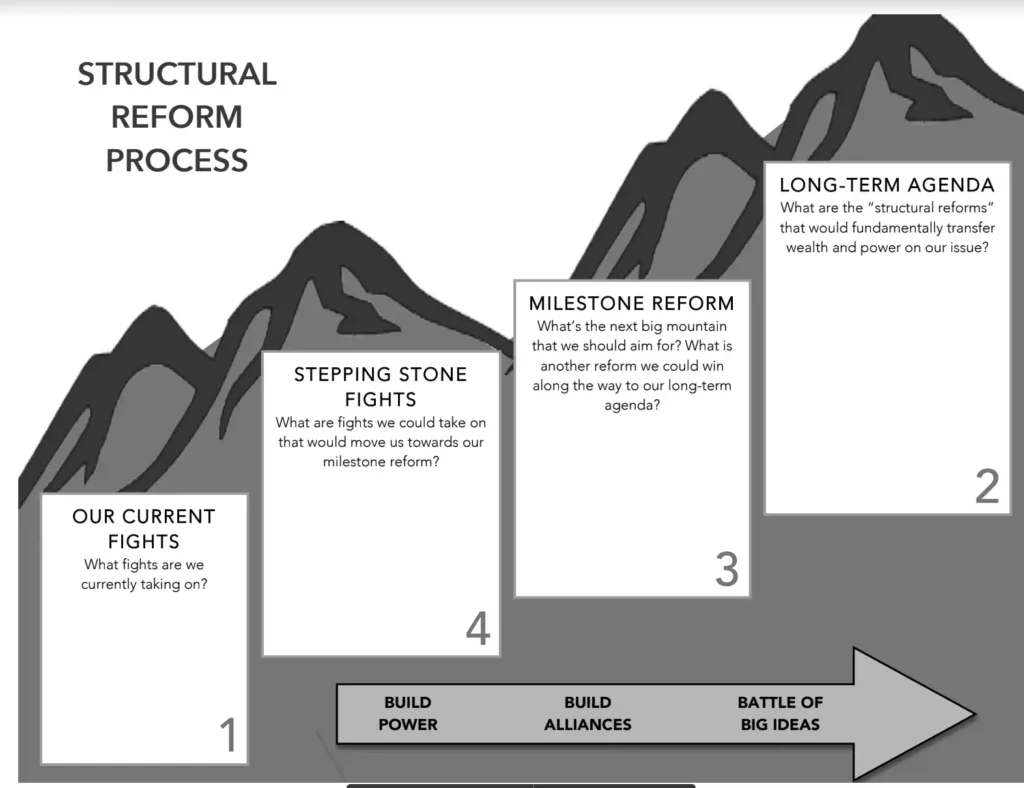

4. Stepping stones. This has to do with the ways that current and future campaigns can move us toward game-changing reforms. Looking at current fights, what are some ways we can use it to move us toward the next level of reforms? And how do we build toward the next level, and the next? Not every campaign has to be a ‘structural’ reform; it should be used as a way to make the space for more structural demands. A shorter-term issue campaign or initiative can become a stepping stone with some changes in campaign and organizing practice.

When working with a long time-horizon, we have found that people need a way to picture a shorter time horizon (mid-range) that is aligned with the longer-term. To this end, we introduced the notion of milestone reforms, or ones that we can aim for 10 to 15 years out. These orient our work, help us see over the next ‘ridge’ toward the longer-term transformations. These milestone reforms help us orient current fights so that they become stepping stones. Without the notion of milestones, it becomes harder to keep track as we move from current fights to stepping stones to transformational change.

Here is one way of picturing the sequencing of campaigns and fights to advance from stepping-stones to milestones to structural reforms:

B. Elements that need to weave through the process of crafting a long-term (or mid-range) agenda:

- Strategic Practice. This is about identifying and making shifts in daily practice, or what needs to be different about the way we are working: existing campaigns, new campaigns, alliances, etc. so that every campaign becomes a stepping stone. Relating this to alignment, it can help clarify a division of labor; we aren’t working on the same things but we are working from the same playbook.

- Ideological struggle. An integral part of changing practice should be working to change the narratives as part of advancing the fights and opening up possibilities for more

structural reforms and political transformations. Shifting the ideological terrain makes it possible to advance beyond the one-off campaign toward advancing the whole picture.

Summary. This overall picture, or LTA, brings together visionary, long-term goals, pathways to advance those goals, and a notion of sequencing reforms along those pathways, keeping in mind that things won’t necessarily progress linearly, nor will they stick to one pathway. Whether we are focused on big changes over the next 10 years or 40 years, crafting a shared, long-term agenda can reorient our work so that it adds up to something bigger. It helps align the work of multiple groups in a shared ecosystem, in ways that allow each group to see themselves in the larger project of moving an agenda, suggesting a division of labor and coordination. It helps identify shifts in practice that move us from short-term work toward a longer time-horizon, and it weaves in our work on narrative and worldview. And while it is good for any kind of organizing group to have a sense of their long-term goals and pathways for achieving them, one thing that the Long-Term Agenda has affirmed for us is that, achieving the levels of change that we seek requires a movement perspective. Crafting an LTA works best as a framework for aligning the work of different kinds of groups and sectors in an alliance or network.